FEBRUARY

LICHENS

📍Northern hemisphere, Lithuania and Tenerife

Welcome to our monthly observational play. We would like to share our tiny glimpses of what plants do in February and focus on relationships with lichens.

Next month — March x Spring ephemerals.

"Thus enlarged, lichens and plants become a world, are transformed into hyperbole – forests, cliffs, escarpments, lunar surfaces – and are revealed in very slow motion as so many silent aerial views".

Vincent Zonca, Lichens Toward a Minimal Resistance

FEBRUARY

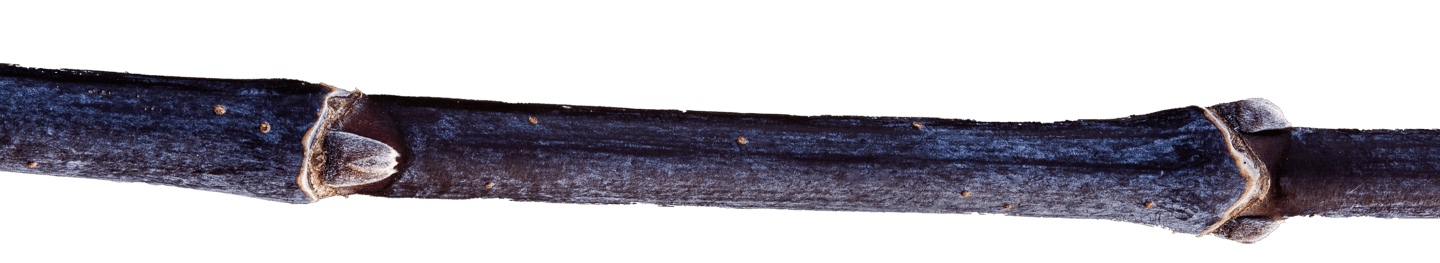

How does your local plantscape look in February? Deciduous forests appear somewhat empty. Have you noticed how newcomer ash-leaved maple (Acer negundo) adds a lilac tone to the scenery? It might appear due to pruinescence — a "frosted" or dusty coating on a surface. It's usually white or light blue, but can be gray, pink, purple, or red. These colors might come from how light scatters.

European beech (Fagus sylvatica) with marcescent, copper-colored leaves quivering in the slightest breeze in Juodkrante Old Growth forest.

Almost all trees lose their leaves in autumn, because of the abscission zone cells at the base of leaf petiole which act like scissors. The true reason why some trees retain leaves during winter is not clear. Because leaves usually remain on younger branches, it is believed that the leaves act as deterrents from browsing animals. Alternative theories point out the protection of buds and water collection or even nutrient storage to use in early spring.

North-oriented slopes or other depressions formed by glaciers have snow and ice cover in February. As we walk around looking for lichens, the forest becomes full of sharp snow crackling. One can also notice the rundown water frozen on the trunk of an old tree. Can the forced extension cause a bark crack? Will the crack become inhabited by some specialized species, looking for the right microhabitat?

A crack formed by the separation of the two limbs, who's wintering there?

What else stand out? Percussion of marcescent (retaining their leaves) young oaks (Quercus robur) and… speckled maps of lichens. Because of the global warming, we will see more marcescent trees in our forests soon as the distribution area of European beech (Fagus sylvatica) moves north.

Fresh lilac stem of ash-leaved maple (Acer negundo)

WHY OBSERVE LICHENS

Winter is a wonderful time for observing lichens, thriving while others rest, they balance photosynthesis and respiration when temperatures drop below 0°C. The best part — they are always around to be seen, noticed, spent time with, and observed.

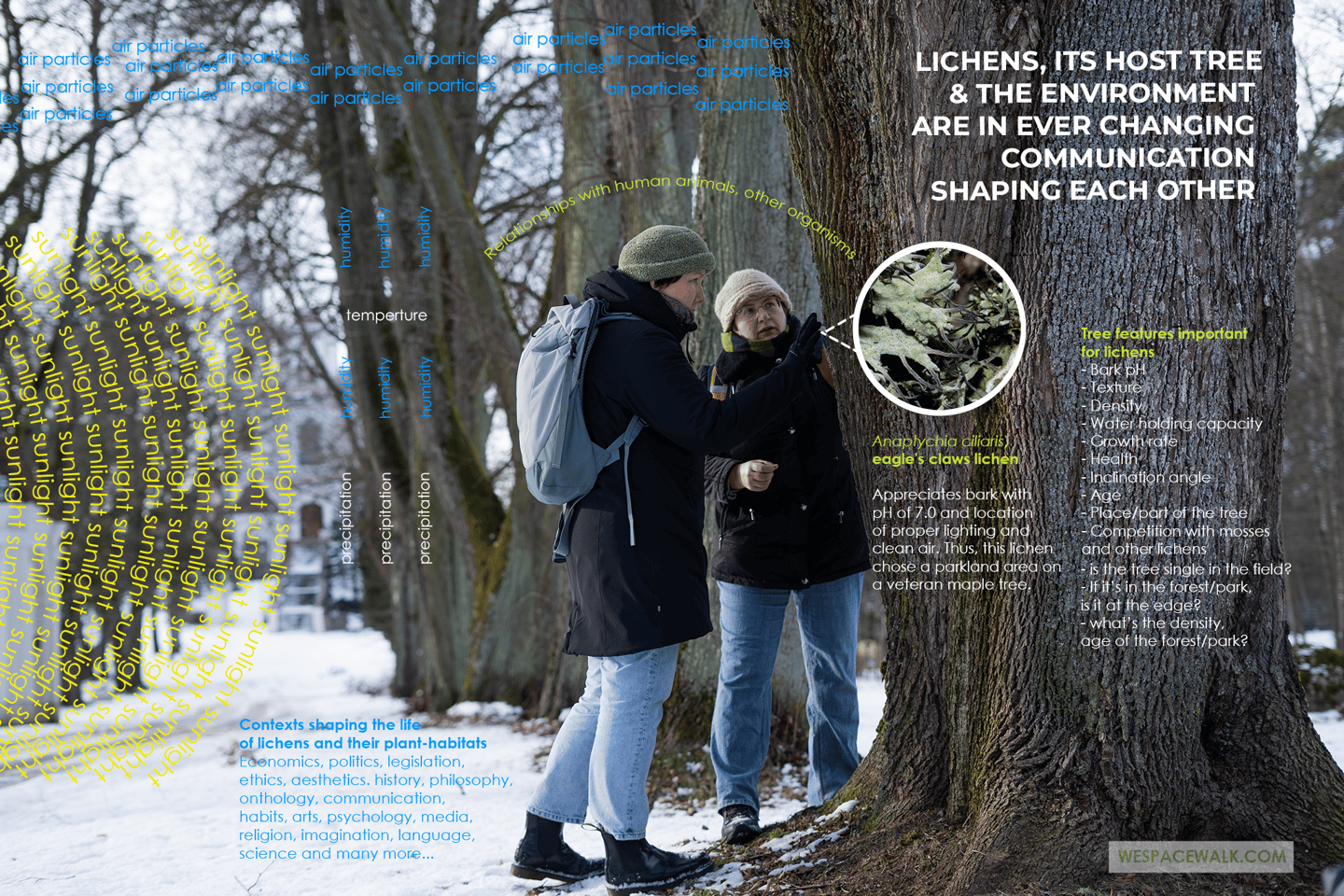

In February's observational play, we're interested in exploring relationships between plants and lichens. To delve into these entanglements, we invited expert lichenologist Jurga Motiejūnaitė for a walk in Vilnius, Lithuania. Each new species we've met, or discussed its environment challenged our perceptions.

While some photos are from snowy Lithuania, others are from Tenerife, which was also a part of our February observations.

Jurga took us on one of her most frequented trails, where she observes lichens repeatedly over the long term. Her keen eye allows her to connect the dots and share how the environment shapes lichen life and how they respond to various microhabitats.

We began by strolling the main street, where young lime trees endure heavy pollution. In conditions rich with nitrogen compounds and ample light, a community known as Xantorion emerges, led by the yellow Maritime sunburst lichen, Xanthoria parietina.

On Vilnius's main street, the lichen community remains similar but with fewer varieties due to increased pollution.

Within these communities, various lichen types compete for light and space, alongside mosses.

SENSING THE HABITAT

Maritime sunburst lichen, Xanthoria parietina, very frequent in cities

We've moved a few steps away from the main street. What do lichens do like plants? They photosynthesize. But can they do it in the shade during summer when leaves are covering all the light? Not really. That's why lichens avoid growing on these tree barks.

Old man's beard, Usnea barbata, absorb the mist drifting from the clouds at higher altitudes in the Corona Forest of Tenerife. These lichens are more sensitive and significantly less resilient to pollution.

Lichens can grow on any stable surface because they are not reliant on their substrate for nutrients. Since birch (white part) bark peels off too often, lichens don't grow there. Interestingly, the slower a tree grows in its early years, the more lichens it tends to have, as lichens don't thrive on fast-growing surfaces.

BARK'S SUBTLE NUANCES

Further from the street, the selection of lichens is completely different, bushy lichens and a larger variety of lichens start to appear.

Do lichens cause degradation of the tree's bark? Not at all, as the tree's bark has a natural ability to regenerate. Lichens don't derive nutrients directly from the bark; rather, they simply utilize trees as a habitat, a place to call home, a support.

A tree closer to the park, further from the busy street

By the busy street

Jurga underlines the importance of context, particularly with lichen species that typically reside on bark. Interestingly, these lichens can also flourish on siliceous stones, benefitting from the extra runoff of nutrients from nearby trees. As time passes, the stone's surface gradually mirrors that of tree bark, inviting lichens accustomed to such habitats to take place, for example, Melanelixia glabratula.

PRETENDING BARK

Melanelixia glabratula under linden tree

Jurga draws our attention to how Lepraria (1) thrives in the crevices of the bark. If it grows on the upper side, it easily peels off, which isn't ideal for them because lichens, as we mentioned before, prefer stability.

When searching for lichens on tree bark, getting up close with the nose almost touching, you'll likely spot other organisms too. For example, one might encounter orange terrestrial algae (2) or green algae (3)!

NEIGHBOURS

1.Lepraria

2.Orange Terrestrial Algae, Trentepohilales (brownish ones)

3.Green algae, Chlorophyta (in the middle)

We've delved into what's probably the hottest topic about lichens — SYMBIOSIS.

Lichens, who are they? It's a fungi, an ecosystem, where fungi have adapted to a unique way of obtaining nutrients and lives with other partners like algae or/and cyanobacteria, yeast, bacteria, amoebas, and viruses.

Jurga strongly emphasizes that questions about "what" and "how much" organisms in lichen symbiosis are interacting are still unanswered, and the relationships between organisms are mostly unknown.

"Society craves symbiosis turning out to be an idealistic uninion exclusive to lichens perhaps even more than it craves cute, fluffy kittens. However, it's crucial to recognize that symbiosis encompasses a broad spectrum, including parasitism, where one organism's survival depends on another's." - says Jurga.

SYMBIOSIS

Symbiotic relationships are inherent in all aspects of life, representing highly intricate processes, it is important to look at them with extra care.

Inner lives of lichens are complex and still challenging for human mind to perceive.

ANALOGIES AND METAPHORES

People have come up with all sorts of comparisons to describe the many identities of lichens, depending on how we see their alliances: a lichen is what happens when a fungus hugs an algae and doesn’t let go, fungi practicing agriculture, a fungal dietary strategy, algal farmsteads, fungal greenhouses.

Vincent Zonca's "Lichens, Toward a Mininimal Resistance" delves into the lifestyles and habits of lichens, exploring how they challenge our understanding of decentralization, interdependence, humility, resistance to exploitation, slowness, porosity, adaptability, diverse forms, and intimate connection with their environment.

For amateurs and beginners, Jurga recommends observing lichens through photography or hand lens rather than collecting their thallus. It's important to remember that lichens grow slowly, and sometimes removing even a 10 cm long clump can destroy an organism that may be 10-15 years old.

HOW TO OBSERVE?

...or learn to trust your eyeballs as Jurga!

What words or metaphors spring to mind when seeing this cartilage lichen, Ramalina fraxinea?

Sometimes it is more convenient to explore windfallen lichens, or twigs on the ground which have been snapped off by winter winds.

Radvile made a good point: being a botanist is like mastering a craft, and it's probably the same for lichenologists. You need someone to show you around to better see and connect, especially with the tiniest, subtle ones.

Chaenotheca ferruginea on a pine tree bark, 0.4-2 mm tall

Pale Leaf-Dot, Fellhanera bouteillei, spotted on a spruce needle. Captured by Jurga Motiejūnaitė

Candelariella aurella spotted on the cemetery's cement fence. You might need a hand lens for a sneak peek, but for Jurga, spotting it is a piece of cake with just the naked eye.

Radvile is checking in with lichens on the cemetery's fence. An observation from Laurie A. Palmer comes to mind: "We blame the lichens for eating the paving stones that line our garden walks, but it’s usually not the well-being of the stones that concerns us". So what's concerning us?

Jurga shares that in Lithuania, one can discover not just new species, but also species that haven't been described in science yet.

We also think it's an opportunity to explore different/similar ways of living and experiencing the world. Understanding how organisms are influenced by their surroundings. How lichens adapt to changes in light, moisture, and air. This constant shift between wet and dry periods is the unique rhythm of lichen life. In fact, within a single type of lichen, you won't find two identical thallus, as each one carries signs of its environment.

WHAT IS POSSIBLE?